|

||

| <--retour / back | NICHOLAS GALANIN |

|

|

||

|

Nicholas Galanin Culture cannot be contained as it unfolds. My art enters this stream at many different points, looking backwards, looking forwards, generating its own sound and motion. I am inspired by generations of Tlingit creativity and contribute to this wealthy conversation through active curiosity. There is no room in this exploration for the tired prescriptions of the "Indian Art World" and its institutions. Through creating I assert my freedom. Concepts drive my medium. I draw upon a wide range of indigenous technologies and global materials when exploring an idea. Adaptation and resistance, lies and exaggeration, dreams, memories and poetic views of daily life--these themes recur in my work, taking form through sound, texture, and image. Inert objects spring back to life; kitsch is reclaimed as cultural renewal; dancers merge ritual and rap. I am most comfortable not knowing what form my next idea will take, a boundless creative path of concept-based motion. |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

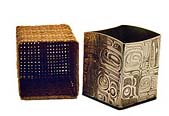

Biography: Nicholas Galanin Born in Sitka, Alaska, Nicholas Galanin has struck an intriguing balance between his origins and the course of his practice. Having trained extensively in 'traditional' as well as 'contemporary' approaches to art, he pursues them both in parallel paths. His stunning bodies of work simultaneously preserve his culture and explore new perceptual territory. Galanin comes from a long line of Northwest Coast artists – starting with his great-grandfather, who sculpted in wood, down through his father, who works in both precious metal and stone. Although Galanin's parents separated when he was a child, he continued to spend important time with his father, especially working together in the studio. The artist looks back on those experiences now as a "very memorable part of [his] childhood" – as this sharing of art became a potent link to his heritage and a vehicle of cultural identity. Galanin's mother is part non-Native and part Cherokee, although, the artist says, he never developed an awareness of his indigenous heritage on that side of the family. After his parents' separation, he moved around a great deal with his mother – to Arizona, Seattle, Washington, Juneau, Alaska, and elsewhere. By the time he graduated from high school, the artist had attended 13 different schools. Having always had an interest in creating, Galanin took on apprenticeships at an early age – first with his father and his uncle, then with other local, traditional artists. When he was about 18, he began to feel the strain of being pulled in two directions – working a day-job, with its requisite frustrations and energy drain, while simultaneously apprenticing in the arts. At that point he realized that he needed to commit himself totally to art-making, or it "wasn't going to happen." From early craft courses, he went on to study at the London Guildhall University (in London, England from 2000 to 2003), where he received a Bachelor's of Fine Arts with honors in Jewelry Design and Silversmithing. Unfortunately, however, the school's curriculum was inflexible, and the artist found it difficult to pursue his innovative, culture-based ideas within their academic structure – so he kept a running sketchbook on the side for planned projects. Soon after, Galanin discovered a graduate arts program at Massey University in New Zealand that meshed perfectly with his interests and concerns, and in 2004 he began earning a Master's degree there in Indigenous Visual Arts. The artist has commented that the Maori have established strong cultural programs, and that their initiatives are of tremendous interest to other indigenous groups. Some of Galanin's most striking works were recently exhibited in an important show at the Aldrich Museum (Ridgefield, CT) called "No Reservations." Among them were his contemporary 'Northwest Coast masks,' adapted to confront cultural issues. One of them suggested a Tlingit mask, but it was cut from a stack of 700 sheets of paper – bound in back like a book and containing the words, "Made in Indonesia." The most obvious of numerous ironies in this work is that its 'Northwest Coast style' is greatly diluted, with its contours much less distinct than in traditional masks. Additionally, it has none of the characteristic form-line design (see Glossary) on its surface, nor is it painted in high contrast colors. Beyond that, its generalized facial features could have been created by another culture (and in fact, the template for this work is actually a copy of a Tlingit mask that was carved in Indonesia). Similarly, Galanin's Tlingit Raven Vol. 14 is cut from the pages of a book. Like the 'Indonesian' mask, it reveals that when we now confront a Tlingit mask, what we see is filtered through foreign documentation and analysis – which have been fed back to both Native artists and their audience. Both of these works retain the elegance of traditional masks, but their contemporary forms have an eeriness, a feeling of being there and not there – perhaps because of their pale color, their blurry, almost shrouded, features, and their seemingly sightless eyes. And, just as they seem to be materializing from the book's pages, they also hover on the point of dissolution. There is an implication that they will never fully take form – resulting in a haunting sense of loss and longing. Also gifted at working in video, Galanin has created a stunning piece titled Who We Are – in which single frames of 25,000 traditional Northwest Coast objects are collapsed into a 15-minute video loop. Silently flashing before the viewer, individual objects are impossible to separate from the diluvian flow. The speed of the piece, and its overload of images, evokes the superficiality of contemporary life, in which complex phenomena are reduced to sound-bytes or media spots. By arranging the art-works according to formal similarities, Galanin makes "categories of objects, such as baskets and bowls, gradually morph into each other" (Aldrich 2006). Fascinating though they are, the flickering transformations create a disturbing sense of moving all too fast, with forms melting into each other at a rate that defies comprehension or control. Despite the power and insights of these works, Galanin is well aware of their draw-backs for him as an indigenous person. On that subject, he has remarked, "Elders have difficulty seeing themselves in pieces such as the generic faces created from [reams of] paper, … though the concept speaks to issues our culture deals with today…" (Aldrich 2006). Similarly, a Tlingit artist's use of a medium like video can be unsettling to Northwest Coast traditionalists. Galanin has acknowledged the personal challenge involved in this kind of art-making: "Tradition is a gift… Coming from a culture with a strong visual language, I risk cutting myself free from this when I work away from these forms" (Aldrich 2006). Valuing his culture as highly as his individuality, Galanin has created an unusual path for himself. He deftly navigates "the politics of cultural representation" (www.nicholasgalanin.com), as he balances both ends of the aesthetic spectrum. With a fiercely independent spirit, Galanin has found the best of both worlds and has given them back to his audience in stunning form. Where to See Galanin's Work Musée D'Art Contemporain De Baie St-Paul, QC, Canada |